PHOTOGRAPHS BY MARK LOADER

Throughout my adult life, my mother and I have spoken almost daily, and while these calls included the usual sharing of jokes, family updates, and invaluable advice and counsel, the last topic before signing off was either what we were cooking that day or a recount of the previous night’s meal. Sometimes, we would simply call one another for culinary advice. It was as if our olfactory senses worked over the phone and we were able to suggest how a spoonful of Dijon mustard would perk up a beef stew, or some dill added to the cottage cheese dumplings that were going into a pot of chicken soup would enhance the broth.

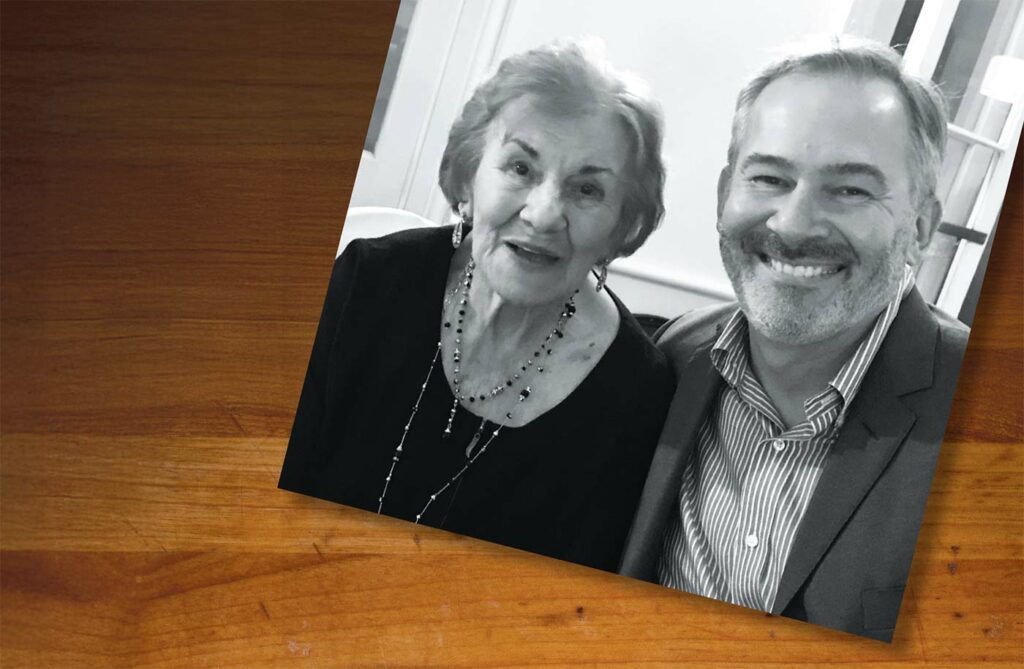

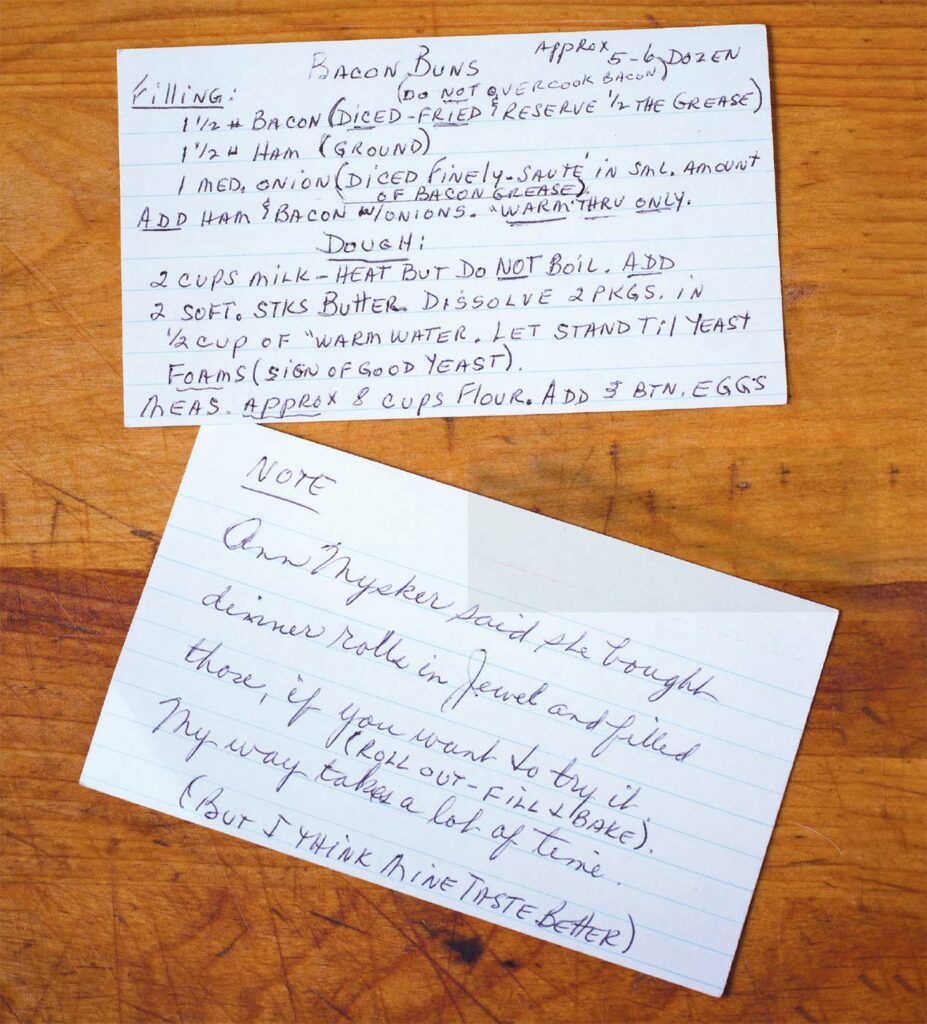

We cooked together across hundreds of miles, so I knew when my mother asked me to come home to Chicago last September, we would spend most of the time in her kitchen. At 97, she was still living on her own in the house in which she had cooked for half a century. However, she was realizing that she may not be able to do that for much longer— an unimaginable thought to her as she loved her independence as much as we loved her cooking. Our visits often included favorite childhood meals: a breakfast of palačinka (a Croatian crepe) rolled with homemade apple butter the way my grandmother used to make them, a lunch of potato leek soup that called to mind being sequestered by winter snow storms, and piroshki—the eggy, enriched buns akin to a brioche filled with sautéed ham, bacon, and onions. My mother learned to make them from a Lithuanian neighbor after she discovered my sisters had been trading their entire school lunches for them. We knew them as bacon buns, but different piroshki—filled with everything from mushrooms and cabbage to meat—enliven the tables of many Eastern European cultures. If Chicago was a melting pot, the burner on my mother’s stove is where that pot resided.

I went off to college in the ’80s, just as the food scene was taking off, but I realized that the food revolution had already happened in my mother’s kitchen. Chicagoans came together at the table, sharing their native cuisines with one another as openly as they shared their love of local sports teams. Polenta, boeuf bourguignon (known locally as burgundy beef ), oxtail soup, tamales, spaetzle, and pierogi may not have been the food of our forebears, but they were a part of who we were. Coming home meant having all these things collectively under one roof, prepared with love.

As excited as I was to visit my mother, I was also concerned about her future. On my ride there, she and I chatted about the food we would make—a pork loin in leek sauce, perhaps served alongside Grandma’s cottage cheese dumplings in brown butter. Or maybe we would make ravioli like the ones we had made at our lake house with my Italian aunt each President’s Day—when my dad’s family would get together to make thousands of ravioli, which were set to freeze on sheet pans on the ski racks of our cars so that they could be packaged and put into the basement freezer to be eaten throughout the year. I also told her that I had a bushel of apples and was hoping to make apple butter to put up for the coming year.

When I arrived home, I saw that there had clearly been a shift in my mother’s well-being. The morning after I arrived, we went into the kitchen to make breakfast, but she let me do the cooking. She already had the coffee maker ready to go, having set it up the night before, and left the plug out of the outlet until the morning just as my grandmother had always done out of fear of an electrical fire. Somehow, I know my mother did not truly think this was an issue, but she honored my grandmother’s tradition nevertheless.

When my sister came over that afternoon, it was evident that the next stage of my mom’s life had come. She was going to need help to stay in her home. We discussed how we could make that happen as we cored and sliced the apples into a giant pot, topping them with a little cider and water and adding the sugar, cinnamon, allspice, and cloves that would add depth to the apple butter. And as the fragrance of the simmering apples filled the house, we plotted out how we could be there in the months ahead, all the while trying not to think about the inevitable.

It was clear that the sustenance that these foods provided was not caloric but spiritual. Thanks to her, these foods will pass down through our family to provide comfort and even a sense of joy in life’s difficult moments.

Over French toast the next morning, our mother regaled us with stories about her childhood—the strudel dough my grandmother would pull across the length of her kitchen table until the dough was so thin it was transparent before adding the apple filling and rolling it up, and of driving with her father to the green grocer to fill a car with fruit to bring to my mother’s relatives, including a five-foot-long hand of bananas. These stories, told to us time and again, were our legacy—a connection to food, fresh produce, and the act of cooking that brought us together.

As the days progressed, it became clear that my mom had called me home to say goodbye. While she was enjoying the potato leek soup we made for her, enriched with a touch of cream and some spinach to give her the sustenance she needed, she was also slowly weaning herself off of the things she loved, all the while taking in everything these foods had to offer her—their memories, the love with which they were prepared, and the flavors that took her back to our childhoods and her own. Always determined, she wanted to end her life in the same orderly, controlled way she had managed her kitchen. As small plates of food fell off to mere bites, we shared our memories of her cooking and baking. I remembered turning the handle on the nut grinder to pulverize walnuts (now I use a food processor) that would be added to honey and whipped egg whites that would be spread across the eggy dough she was rolling out to form a potica, which we knew as walnut cake. And my sister recounted how my mother used kolache dough scraps to teach us how to use the rolling pin to get the dough to an even thickness. When my other sisters visited, they, too, shared the skills they had taken in over the years cooking with my mother. My mother would live on in these actions once she was gone, the way her mother lived on for her when she unplugged the coffeepot each morning, not for fear of what might happen but for fear of what might be lost should she not carry on.

In the final days before my mother stopped eating altogether or even taking in any water, she would ask for a sip or two of leek soup in a coffee cup with a picture of two of her great-grandchildren on it, or take in a few forkfuls of a palačinka, its apple butter filling redolent and spilling onto the plate. It was clear that the sustenance that these foods provided was not caloric but spiritual. Thanks to her, these foods will pass down through our family to provide comfort and even a sense of joy in life’s difficult moments. And perhaps I need to put away my food processor and buy a hand-cranked nut grinder—and make sure I unplug the coffee maker.