Preserving open space—and producing local food—amid an evolving landscape

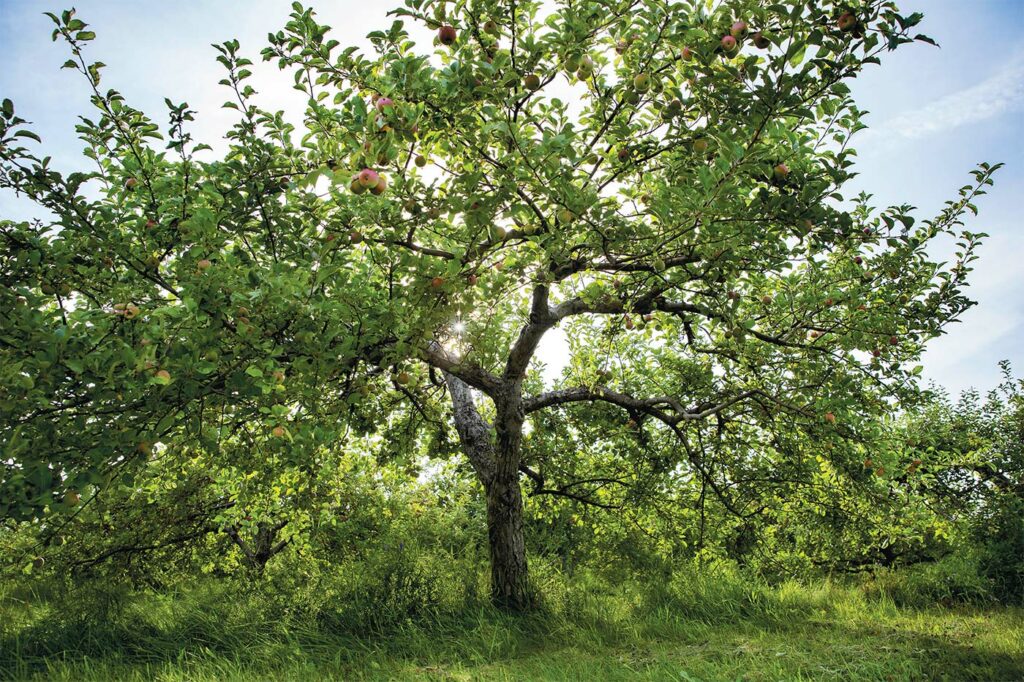

Despite the crisp, juicy crop being synonymous with fall in the 413, conditions for growing apples in the Berkshires are far from ideal. Last May at Riiska Brook Orchard, after an unusually warm spring that caused fruit buds to swell several weeks ahead of schedule, Emily Melchior and Calvin Rodman watched in awe as more than 1,600 apple trees in nine varieties blossomed for the first time under their ownership.

Just weeks later, a dramatic cold snap decimated their 2023 apple crop, shedding light on a persistent challenge for growers of seasonal crops. “Fungal and pest pressure in the Northeast make growing apples here harder than you would think,” says Emily, referring to the invasive spotted lanternfly and fire blight, both of which can wreak havoc on a crop in very little time.

Yet while the bounty of Macs and Cortlands will be missing this fall, the couple remains focused on the positive: their ability to preserve the orchard’s sprawling open space from development while prioritizing the painstaking process of local food production. “It feels like this is a great apple-growing region, because they’ve always been here, but it’s far from easy,” says Calvin. Add mid-May’s historic frost event to the equation, and any apples plucked directly from the tree this season might be miraculous.

“Overall, we lost 75% of this year’s crop,” he says, pointing to a pair of extremes: low-lying areas where the trees are bare versus pockets on the sloping hillside where everything appears normal. Adds Emily, “We held out hope for a period of time after the frost that the damage wouldn’t be too severe,” explaining that it took some time, given the apples’ advanced stage of growth, to realize the extent of the damage. Despite the grim prognosis, their efforts are hardly for naught: Almost a decade after purchasing property in the bucolic albeit tiny town of Sandisfield as a refuge from New York City life, Emily and Calvin cite the increasingly volatile weather as yet another challenge of producing food in the Berkshires. But they choose to focus on keeping one of their community’s amenities open to the public for the sake of posterity.

“Bill [Riiska] was adamant that the property be preserved as an orchard, and not developed, which is what would have happened had [the business] been put on the market.” —Emily Melchior

PRESERVING THE LAND

August marked the first anniversary of the couple’s acquisition of a business begun more than three decades prior by the orchard’s eponymous founders who, in 1990, were inspired to plant a few apple trees on the 140-acre former dairy farm where Bill Riiska was raised. Today, it remains a destination for local residents and visitors from near and far alike, most of whom seek solace in visiting the property, picking apples, and making memories in the process.

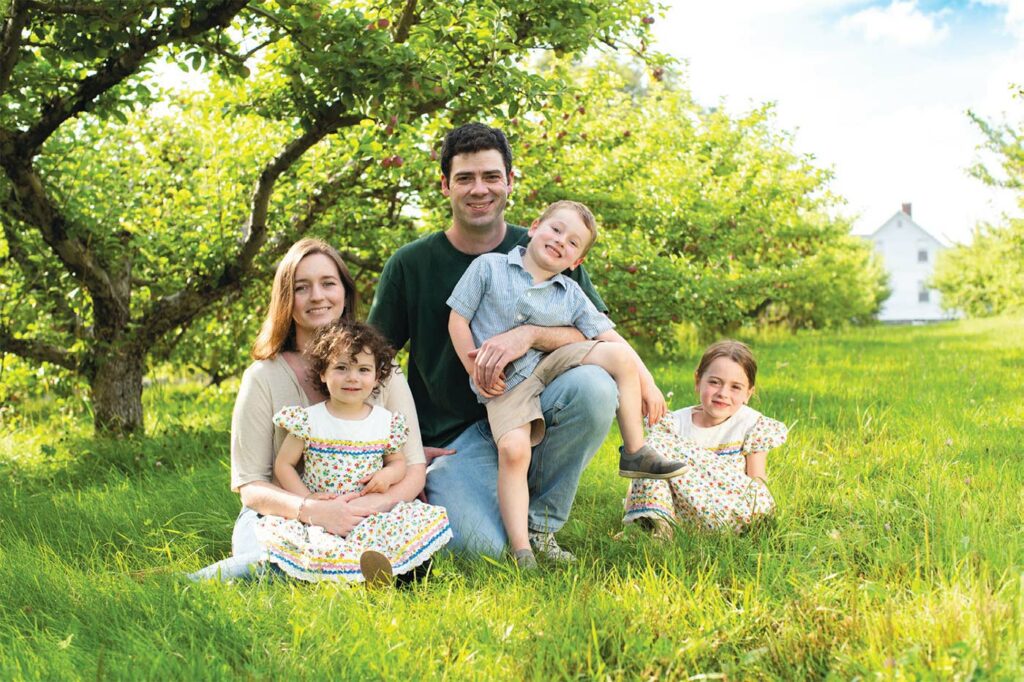

“We think of it as a park-like destination and we try to create a relaxed atmosphere where people can just be here and enjoy the space,” Emily says. While Calvin tends their kids and the orchard, Emily has a hybrid work arrangement for a New York–based finance company, so they have the resources to maintain the orchard as a community space, at least for the time being.

“Bill [Riiska] was adamant that the property be preserved as an orchard, and not developed, which is what would have happened had [the business] been put on the market,” says Emily. Soon after settling in Sandisfield, the gnarled tree trunks dotting the landscape beckoned the new homeowners (whose family has grown to include three children, ages 2, 4, and 6), to explore the local gem of an orchard turned community gathering spot.

“We visited within that first year and have always thought it was a really special place,” says Emily. And while purchasing an orchard was not in their plans, the couple did become aware of the opportunity very quickly via word of mouth, which—they soon learned—travels fast among the small but connected population in town. Living just a mile from the orchard, Emily and Calvin were keenly aware of what could happen if the property was sold and sliced into parcels: The scant mile along New Hartford Road boasted enough frontage for a dozen or more building lots. So they purchased the orchard last year with little experience but loads of determination to learn the ropes and preserve the iconic destination for future generations.

MANY HANDS MAKE LIGHTER WORK

Many of the skills needed to keep an apple orchard up and running—from miscellaneous carpentry to clearing land—overlapped with those Calvin had gleaned restoring the couple’s 1839 home, which was in “very rough shape” when they bought it. If the ensuing year taught them anything, it’s that many hands make light(er) work when it comes to maintaining an orchard. Pruning, an annual task, took three pairs of hands wielding pruning shears two months to complete; and pollinating required rented beehives from Granby, Connecticut. Growing apples and getting them to market—no matter how local—indeed takes a village.

Larger farms with deeper pockets have the infrastructure to employ crop-saving measures like propane heaters and sprinkler systems in the event of late frosts; the latter spew water that creates natural insulation as ice, which protects the apple blossoms and fruit. But Emily and Calvin have sought advice from experts at the UMass Extension Fruit Program, whose mission is to assist fruit growers with all aspects of commercial orchard, vineyard, and berry production and whose members held a twilight meeting at the orchard in May to discuss pest management strategies and sprayer calibration. And they hired an orchard consultant, as a means of creating a far-reaching support system while strengthening their knowledge base.

Emily credits their consultant as tremendously helpful in educating the pair about pest and fungal pressures unique to the area and how best to govern them— including leveraging data, to take a science- and fact-based approach to managing complex issues. For instance, “Our consultant comes out and sets insect traps to see what kind of insects we have and what’s a problem and what isn’t,” Emily says. “And toward the end of the season, she’ll help us determine when the crop is ready and the properties, such as sweetness of specific apples.”

She cites both the consultant and UMass as integral in introducing them to the regional community of orchards and specialists that help make their work of growing apples in the Northeast possible.

“The industry as a whole used to be much bigger in the region, but there’s still a robust support network [and] lots of people who are still working hard to make [growing apples] work here,” says Calvin, referring to the Stockbridge School of Agriculture at UMass Amherst and the New York State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell. In an era marked by myriad family-owned and -operated farms shifting their focus to stay afloat, Emily and Calvin are committed to preserving what folks love about Riiska Brook Orchard: an abundant open space for gathering with friends and family. Having survived their inaugural season, the second full growing season remains rife with residual growing pains.

“Especially for us, during this [ongoing] transition period, a concern has been introducing people to the orchard for the first time and having a less-than-ideal picking experience,” says Calvin who, despite this year’s dicey crop, feels lucky to have a loyal customer base that doesn’t want to see too many changes. Last year, he and Emily invested in new cider-making equipment for pressing (and bottling) the fruits of their labors on site; this year, they’ll also sell honey from their rented bees. And they will continue the annual tradition of welcoming young students from nearby regional schools and daycares.

“We’re excited about the future of the business and what that looks like,” says Emily, who, after a brisk berry business in July and early August, enjoys looking ahead. Any changes down the line—whether increasing their offerings or expanding ways to accommodate people who just want to spend time at the orchard (when the blossoms are out, for instance)—will be incremental.

“As we think about the evolution of the orchard, it’s about having a viable business that adapts to the needs of our customers,” says Emily. “We want to hear feedback from them about what they want.”

“We think of it as a park-like destination and we try to create a relaxed atmosphere where people can just be here and enjoy the space.” —Emily Melchior