Kevin West Celebrates the Seasons

In late winter or spring, a conversation with Kevin West, the author of The Cook’s Garden, would naturally focus on the planning and planting of the vegetable garden. The topics would range from best practices for nurturing seedlings of favorite heirloom tomatoes indoors before they can be set out, approaches to crop rotation to minimize pest and disease issues, and methods for determining the timing of direct-sown cool-season crops, such as peas, beets, and lettuces, and later of direct-sown crops that prefer the heat, such as beans and cucumbers. But in the fall, the mind does not wander so much to seed selection and timing as it does to harvesting and making the best use of crops both for fresh eating and for preserving. “I love experimenting with varietals in my garden and in the kitchen,” West says. He also takes notes on what makes the cut for future seasons.

Perhaps this is why West’s new book is being released in the fall. If spring is when a young man’s fancy turns to sowing peas and lettuces and preparing for the seasons ahead, the fall is a more contemplative time in the garden, as the harvest is prepared both for immediate eating and for preservation as jam and pickles, and even simply prepped and frozen for eating in the months ahead. West’s previous book, Saving the Season was a primer for first-time home canners, and serves as a self-help book for novice preservationists worried about food safety. West believes that botulism can be kept in check primarily through hot processing—and he also has another approach that lessens the daunting nature of preservation. “Living alone, I find that canning in small batches suits my needs and makes it all more manageable,” he notes. He thinks the same advice is true in the garden—start small and grow what you love with care.

The current volume says volumes on caring for soil, no-till gardening, and building a compost pile. West recommends preparing a new bed in the fall by covering it with cardboard and compost to suppress weeds and to get earthworms to do the work of turning the compost into the soil below so it can be planted the next spring. But the book, undertaken after West’s move from Los Angeles to Monterey in the heart of the Berkshires, promotes not only the act of gardening but the act of living from the garden.

Back in Laurel Canyon, West was dependent on local growers and the farmers market as a source of produce for the pickles and preserves that filled his previous book. “I only had a small amount of space in a tiny yard where I could grow some lettuce and a few other favorite species,” he recounts. Upon arriving back East, he returned to his agrarian roots (his grandparents’ truck farmed and his parents gardened in eastern Tennessee) and is growing what he can. Although considerably further north with a shorter season, he has been able to grow some of his favorite crops, and in greater variety.

Biodiversity is of great interest to West, and when he says that he loves growing potatoes, he does not mean just growing a few Idaho whites. His passion for potatoes ranges from heirloom fingerlings and purple-fleshed varieties to newly selected cultivars from specialty growers. Like selections of winter squash and apples, each variety has an ideal use and a prime time to be eaten. Understanding what stores well is key to selecting what to grow. Some squash such as delicata are best eaten early in the season (skin and all) whereas others, such as the hard-skinned blue Hubbard, store well and can be eaten later in the season when thinner-skinned varieties have gone soft and succumb to rot. West opines that the stewardship of all these varieties is critical to our access to local produce throughout the seasons and pleasurable to our palate, whether being eaten in season or preserved for the coming months. He also embraces the serendipity of the garden when weeds come into their own: “Good King Henry and purslane are unexpected crops that fill out the salad bowl,” he says. In his previous book, he even shared a recipe for pickled purslane.

And while West can grow a broad array of vegetables and fruits in the Berkshires, others still elude him as his high-elevation garden does not give him ideal conditions for longer-season and heat-loving crops such as melons and okra. While melons and okra connect him back to his grandparents’ truck farm, he realized they are better grown by others in warmer locations, both closer to sea level and further south. When he sees them at the market, he purchases them (for both eating fresh and canning). He also goes to the farmers markets for another reason: to see what local farmers are growing, so that he might better understand what is likely to prosper in his own vegetable garden. He has learned what to grow and how to grow it from Max at MX Morningstar, Pete Salinetti at Woven Roots Farm, and Liz Keen of Indian Line Farm, but he is also happy to continue to support them and others by purchasing vegetables that he does not grow.

West also likes to make sure gardeners realize that home growing does not need to mean growing everything you eat. “Grow what you love most, what you can grow well, and what benefits from being eaten straight from the garden,” he advises. He, for instance, would never be without greens in his garden, because he loves heading out and collecting the makings of a salad in the late afternoon. And he also enjoys lettuces braised in cream when he tires of salad. Alternately, a variety of bush and pole beans provide legumes for eating late into the season and for putting up as pickles.

Living out of the garden is a delicate balancing act between deciding what to grow for the moment and what to harvest and put up for the season ahead. It seems that West has worked it all out for himself, but there is another component of his approach to the garden (and to selecting items from growers in the region at the farmers market) and it seems to connect the American agrarian and pioneer identity: Savor the present, hold onto something of value for the future, and plan for the years ahead as you harvest your bounty. And be thankful for all that is before you.

FEAR OF GETTING CANNED

One of the things that holds gardeners back from putting up jams, pickles, and vegetables is the fear of contamination and a concern for food safety. West works to assuage these concerns by sharing statistics on the rarity of such issues and then states how simple it can be to prevent contamination based on an understanding of acidity, sugar, and salt as bacterial retardants and the use of hot-water baths to sterilize the end product.

While novice canners have a fear of the logistics of sterilizing jars and lids and ensuring the proper seal, West has an approach for most canned goods that involves beginning with jars washed in hot, soapy water that are then filled and topped with lids that have been set in boiling water. The subsequent hot processing (usually about 10 minutes of being submerged in water at a rolling boil) is enough to prevent bacterial growth.

There are a few items that one may want to approach differently so as not to overcook the contents (crunchy pickles and berry jams come to mind), but there are a number of ways to ensure that the final product does not lose its luster. The simplest method is to put the jars in a water bath that is below boiling but above 185° for a longer period until the temperature of the contents of the jars reach 180°, which varies based on what is being processed. And, as West likes to remind people, “When you are making small batches, one can just store many items in the refrigerator if they are going to be used in the short term, and skip processing altogether.”

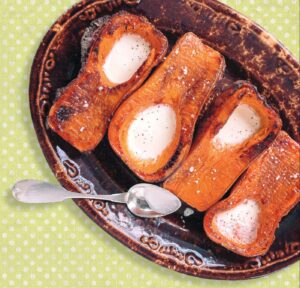

Photo by Kevin West.