Local Farmers Are Adapting and Innovating

Missy Leab of Ioka Valley Farm in Hancock, Massachusetts, told me years ago that we need to revise the farmer’s saying that corn should be knee high by the fourth of July, or that Memorial Day weekend is the time to plant home gardens. For the maple syrup–producing Leabs, who have run their farm together for four generations, “the old-time farming, where you boil on the first of March and you’re done by the first of April—those days are gone,” says Missy. Eleven years after that prescient conversation, climate change increasingly bedevils local farmers’ ability to plan while playing havoc with farm profitability.

The impact of climate change on farming also affects us as food consumers and as amateur growers. What will climate change do to the juicy Sungolds and Early Girl tomatoes trellised in our backyards that we love to pick in August? Ben Crockett, program manager for the nonprofit Berkshire Agricultural Ventures, says that he hears the same thing from both neighbors and the farmers whom he helps shepherd through climate change planning. No one had great outdoor tomatoes in 2023, for example. “The only farmers I know that had success, and the one neighbor I know, did so because the tomatoes were in high tunnels or greenhouses.” That summer the rain never stopped, Crockett explains, causing nutrients to leach from the soil.

UNCERTAINTY POSES CHALLENGES

Sara Kelemen, New England soil health specialist at American Farmland Trust who spoke at a conference Crockett organized on “Farming in a Changing Climate,” confirms Leab’s observations. “We’re moving into a time where farmers are going to have to throw out the calendar they used to rely on and make complex management decisions at a rapid pace,” she says. “We’re not going to know that we’re going to have enough water, or too much water, or whether it’s going to be hot for a long time, or how many storms we’re going to get any year. Essentially, we’re asking more from farmers than ever before.”

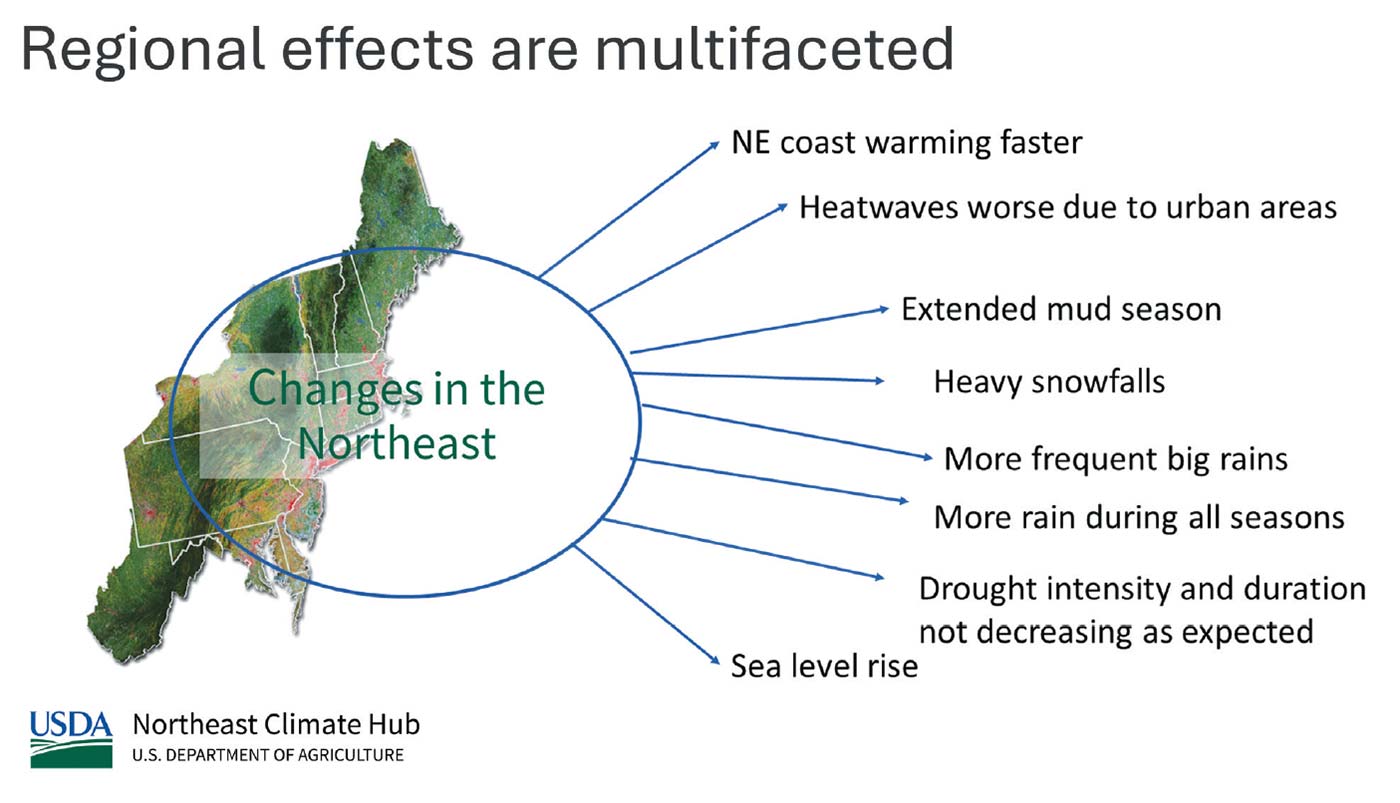

In the Northeast, Kelemen explains, the average regional temperature has increased by three degrees since the ’70s. But it’s not just the earth’s warming that’s problematic. “We’re losing our lowest temperatures,” she says. “Winters are getting warmer and nights are warming more rapidly.” It makes a difference, for example, to farmers who need cool growing conditions, or [who] grow perennials that have adapted to pre–climate change temperatures. And, she says, “We are used to snow cover on the ground. But winter and night warming means we’re getting less snow and more rain. And that’s hard on the soil. That means taking better care to make sure the soil’s covered so we’re not losing it in these winter rainstorms.”

A warmer atmosphere can hold more water, but the issue is not just more rain, it’s that it won’t be spread out among equal, gentle rainstorms. “We’re going to get these extreme weather events,” Kelemen says, including a projected 10% to 15% increase in extreme spring precipitation in western Massachusetts. “Spring is a critical time for farmers,” she emphasizes. Driving a tractor, or even walking on overly wet soil leads to compaction, which negatively impacts growth because plant roots can’t permeate the compacted layer. And when water falls onto that soil, it’s more likely to run off.

But here’s the kicker: Even with more water in the Northeast, drought is not decreasing. The problem is not just oscillating weather. Its unpredictability and the unevenness of the precipitation results in an unseen challenge for farmers: decision-making fatigue. “It’s wet one year, one year it’s dry,” Kelemen says. “The next year there’s a bunch of extreme rain events. The next year, there’s a late frost that kills apple blossoms. Over five seasons, farmers must deal with five wildly different climate impacts that have never been seen before. I think that takes a psychological toll.”

Livestock farmers aren’t spared climate change’s effects. Crockett says that more humid summers from increased moisture in the air raises the heat index and stresses livestock.

MARGINS AND MENTAL HEALTH

Alyssa VanDurme, business members program manager at nonprofit Berkshire Grown, also counsels farmers and is the proprietor of newcomer Field of Love Farm in Sheffield. She, too, is aware of the mental stress on farmers from climate change. “Say there’s a flood and you lose cropland or a crop about to be harvested. Obviously, that’s financially horrible, but if you are someone who prides themselves on being a good farmer, and you’ve put God knows how much work into that crop, it gets to you.” VanDurme notes, “I’ve experienced that myself. The conditions aren’t right, you spend time and money doing something, and you lose it. It eats away at the business and at the sense of achievement.”

Another fallout of climate change: the increase and changes in the type of pests that besiege farmers as a result of warming. Crockett notes that growing potatoes, for example, is getting trickier, especially for organic producers. “The number one pest for potatoes is Colorado potato beetles,” he says. “Because of warmer winters, instead of two to three generations of beetle, we get four, maybe five.” He says that it “has gotten to a point where I know farmers that are not growing potatoes. And that used to be a staple crop—that’s one of those crops they can sell through the winter.”

Livestock farmers aren’t spared climate change’s effects. Crockett says that more humid summers from increased moisture in the air raises the heat index and stresses livestock. “So that means if you’re a milk producer, less milk, and if you’re a meat producer, the animals don’t gain weight. It takes more calories for them to regulate their body than to put on mass. And conditions for flies can get bad.”

Dairy farmers often love it when there’s lot of rain, says Margaret Moulton, executive director of Berkshire Grown. “The grass grows green and thick, and cows love that. But after too much, it can have a deleterious effect. The mud gets stuck on the cows. There could be more fungus, among other things related to sustained dampness and too much water. And dairy farmers run on a wire-thin margin. So, if there’s too much loss, they might say, ‘I can’t do this.’” As Berkshire Grown’s VanDurme graphically puts it, “having helped care for livestock, I can tell you that being knee deep in animal manure in February when it’s 50 degrees is not fun.”

While livestock producers need to think about shading animals on hot days, all farmers must consider how heat affects their and their workers’ ability to farm. “We’ve had to shift our schedules to get out of excessive hot days. What do you do,” asks VanDurme, “when you’re trying to pay commuting staff and want to take four hours off in the afternoon?” Workers either must go home and come back, find something else to do, or work through the heat. “You’re often going in the barn or shade to do easier tasks or ones that may not be the most critical.”

CREATIVE SOLUTIONS

Tough farming tales aside, all is not lost for farming in the Northeast, including western Massachusetts. To put climate change in perspective in this area compared, for example, to the West, Kelemen says “We’re going to be okay. It’s not going to be over 100 degrees every single day in the summer. Agricultural production can continue in the Northeast.”

And there’s plenty farmers can do, as well as what we, consumers, can do, to mitigate the effects of climate change and support food producers. The farmers and experts I spoke to tout soil health as the number one key to resilience, achieved among other ways through no-till farming, which disturbs the soil less, as well as allowing it to hold carbon that would otherwise contribute to global warming.

“It’s like stretching a rubber band until it snaps,” says Crockett. “Improving soil health gives you more stretch, more ability to snap back after extreme events. It’s not a guarantee but an insurance policy.” After no-till, on his list of the top three strategies for farmers is risk planning for climate change and implementing good business practices—having your books in order so that you know what you can fix. “If you say, ‘Farmer Jane, you should use this no-till planter, it’s going to cost you $20,000,’ if Farmer Jane doesn’t know if she can afford or finance that, then she can’t make that choice. If you don’t know your cash flow, if you don’t know your operating expenses, all things any business needs to know, it can be hard to understand where you need to leverage your resources to address risk.”

Meg Bantle, who farms Full Well Farm in Adams with partner Laura Tupper-Palches, is mightily aware of the impact of climate change. Full Well is less than two acres, and while there’s a tractor on-site, the two don’t use it in the field; instead, they practice “handscale” farming. Being no-till is a key adaptive practice. “We’ve seen time and time again, even in six years, how no-till has helped us to be resilient during times of drought, times of flood, given how erratic rain patterns are,” says Bantle. “Just this summer, we had four weeks with no rain and we need soils that are not dried out by tilling and prepared to hold some moisture.” Full Well goes beyond organic, eschewing even organic-certified pesticides because they prefer not to spray. That helps protect local pollinators.

To maintain profitability in the midst of climate change, Bantle says they must be strategic about their crops, for example, growing root vegetables to sell fresh, which command a higher price than when sold as storage crops.

Climate change also means more infrastructure. The possibility of drought demands irrigation, Bantle says. New pests traveling north and others not dying off in winter necessitate row cover, and more indoor growing space helps protect against erratic frosts. “Even though the weather is getting warmer, we have years like last year where a late frost can devastate an early season if you have tomatoes outside,” says Bantle. “So, we are investing more into greenhouses and tunnels that allow us to better control the climate we’re giving crops.”

“If you don’t support farmers, you’re going to lose them for future seasons. No farmer is going home rich from a farmers market. They are trying to make a profit on their bottom line.” —Margaret Moulton, executive director of Berkshire Grown

A NEW NORMAL

There is a rainbow, of sorts, in this saga on the impact of climate change on farmers. Ironically, warmer weather allows farmers to offer products they couldn’t easily grow before. “We’re more consistently harvesting pawpaw, a native Northeast fruit, which historically wasn’t feasible,” says VanDurme. On the other hand, she says, “we’re having a harder time keeping our brassicas—cabbages—cold season crops, from bolting, but in exchange we might have more melons or other tropical fruit.”

As for Missy Leab of Ioka Valley Farm, I caught up with her in late October while she and her husband, Rob, were attending a Portland, Maine, conference on climate change and the maple syrup industry. New technology, she says, is now enabling farmers to take advantage of possible January thaws, allowing them to leave taps in for 12 weeks rather than the more traditional six. Nonetheless, she says, “Climate change is still a moving target.”

Every farmer, it seems, must be prepared to adapt continuously. Jim Schultz, owner of Red Shirt Farm in Lanesborough, has switched up lettuce varieties to those that do better in high-heat summers. He says there are varieties of vegetables that thrive down South that may come North, although he admits he hasn’t given thought yet to growing something like a Southern peach. That being said, he feels that customers willing to buy local will be treated to hundreds of varieties of winter squash beyond the standard butternut and acorn. The Georgia Candy Roaster, he says, is a gorgeous two-foot-long fruit, while the Koginut is a cross between kabocha and butternut that he also produces. “I would encourage people to explore,” he says.

As consumers, we need to remain not only open minded but empathetic.

If we are assiduous about buying local, we’ll contribute to the market success farmers need to maintain their operations. For instance, apple growers had a difficult season in 2023 because of frost, but 2024 has been hugely productive. Buy the apples farmers have now, says Moulton, even if they may be a bit more expensive, because orchards are trying to recoup some of last year’s losses. “If you don’t support farmers, you’re going to lose them for future seasons,” she says. “No farmer is going home rich from a farmers market. They are trying to make a profit on their bottom line.”