It’s early spring and Jim Schultz and I are standing in what will become the farm store at his Red Shirt Farm on Route 7 in Lanesborough. Ripley, one of two farm dogs, is barking outside while an electrician is drilling. Over the din, Schultz is telling me that the store will be open for the summer despite taking longer to finish than expected.

But waiting to realize his dreams is not new for Schultz; he has been practicing that particular brand of patience for most of his adult life. After spending 26 years as a science teacher, track and cross-country coach, and technology administrator at Pittsfield public schools, in 2015 he retired early with a small pension and pivoted to pursue his long-simmering ambition—farming full-time on his own regenerative farm.

Schultz, originally from Winchester, Massachusetts, enrolled in Williams College in 1980 as a pre-med student. But he acknowledges that medicine was never his heart’s desire. While on winter intersession at Merck Forest & Farmland Center in Vermont, he met someone who had studied at Vermont’s Sterling College, which focuses on agriculture and ecology. “He was teaching us how to pull logs and things like that,” says Schultz. That’s when he realized, “This is what I want to do.” Schultz left Williams and spent a year at Sterling. Then, increasingly focused on agriculture, he spent three years apprenticing at New England farms before enrolling in the Ecological Agriculture program at Evergreen State College in Washington.

A DREAM DEFERRED

Along the way, while farm-sitting for the owners of Caretaker Farm in Williamstown, Schultz met and married the owners’ daughter, Annie Smith. Knowing that it would be difficult to support a family on a farm income, he got a master’s in education at UMass-Amherst, while Annie became a registered nurse. The pair raised their two children for several years at Caretaker before, in 2000, buying and combining three parcels off Route 7 into what is now the 10-acre Red Shirt Farm.

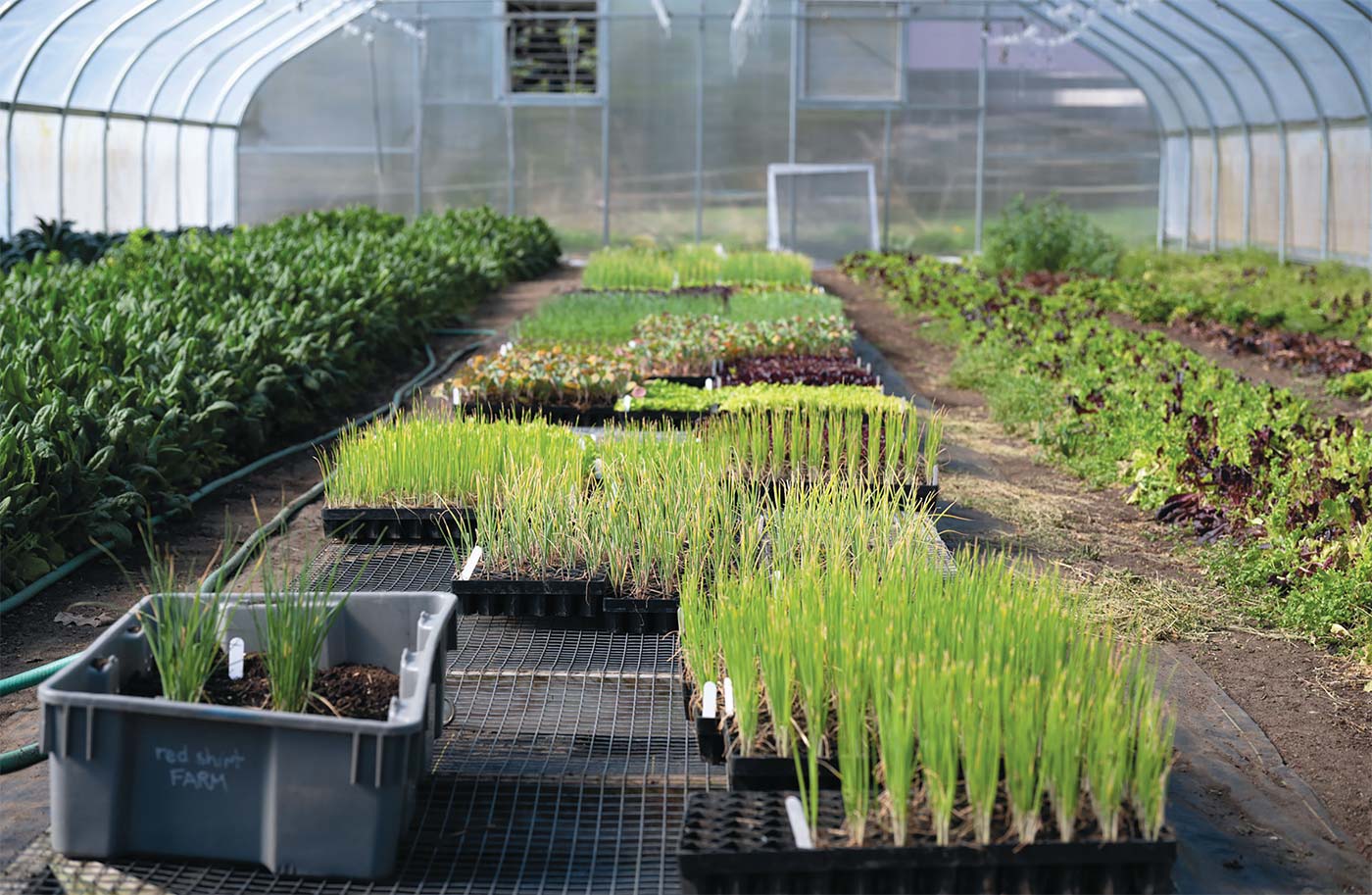

But it wasn’t a farm then, just a family home on hilly, weedy land that was part dumping ground for the former owners who had been in the floral business. So Schultz and Smith cleared the land, planted trees, and developed the soil, installing irrigation and greenhouses, and starting a tiny CSA, all while pursuing their day jobs—Smith as a nurse at Berkshire Medical Center and Schultz as a teacher. “We farmed before school, after school, and on weekends,” recalls Schultz.

Schultz’s path to full-time farming took decades and included studying and attending conferences on alternative and regenerative farming, permaculture, and biodynamics, all while continuing his career in education. He is nothing if not patient, and that trait is what lies behind the farm’s unusual name. As a football, basketball, and track athlete in high school and college, Schultz was familiar with the practice of “redshirting,” in which promising college players in need of further training are allowed to practice but not play with the team. “Why don’t you call it Red Shirt Farm?” Schultz’s sister-in-law, a farmer herself, suggested. “You’ve red-shirted for 25 years waiting to do this.” And so Red Shirt it was.

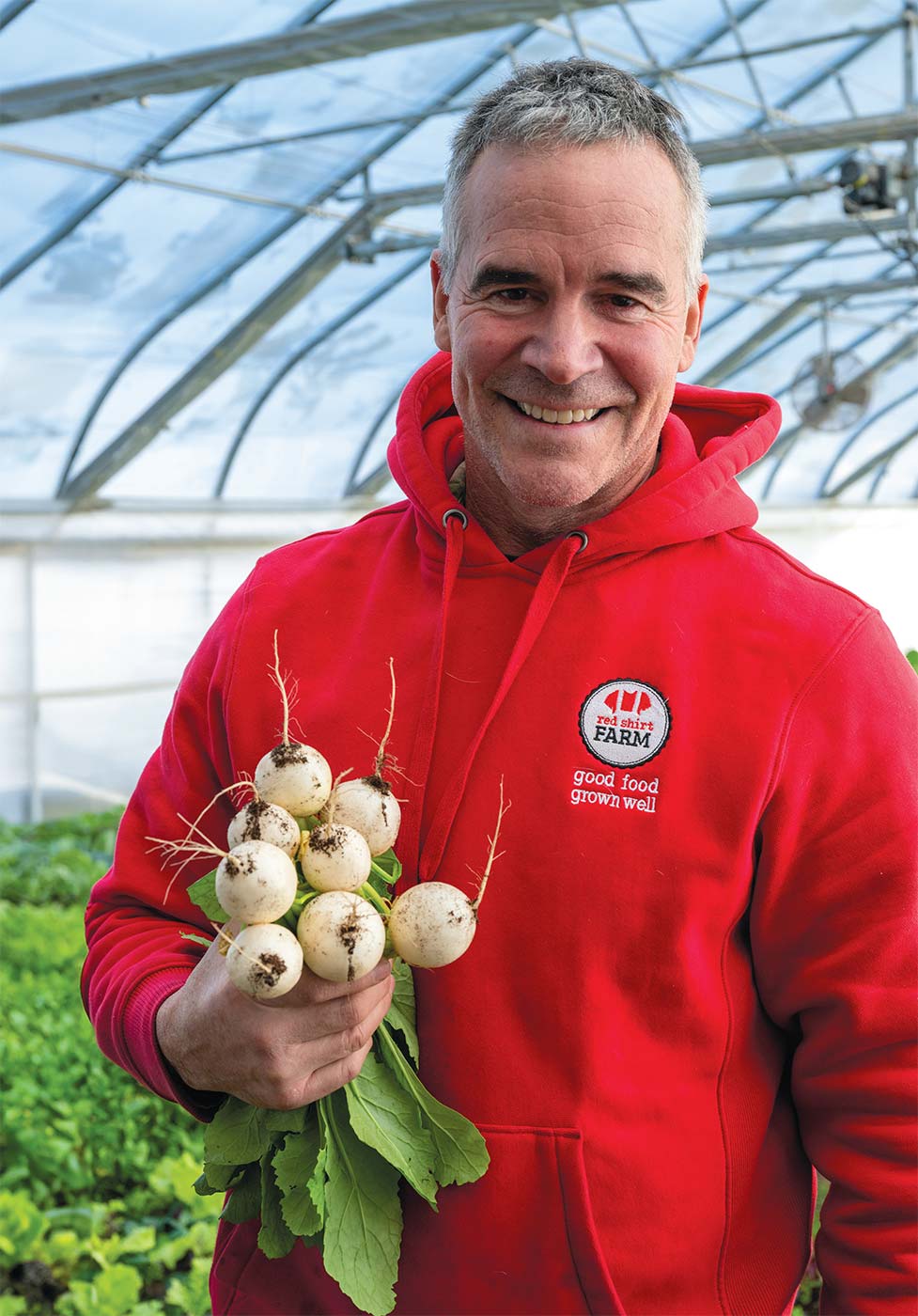

Today, Schultz, who is no longer with Smith, grows 40 varieties of vegetables and herbs on two acres and leaves the rest, including an additional three leased acres, for rotational grazing for his pigs, heritage chickens and turkeys (the latter are on hold this year, given how much is going on). Walking through a greenhouse at Red Shirt, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the geometrically exact rows of lettuces, kale, and turnips—dazzling, intense green intermixed with muted purple. Schultz pulled some young turnips for us to try; we roasted them that evening, and they were perfectly sweet and tender.

A GOOD STEWARD

When we visited Schultz, he was wearing a Red Shirt sweatshirt with the slogan “Good food. Grown well.” For him, that means growing food based on regenerative principles. “By being a good steward of the land, we create a soil that holds more water, is less prone to erosion, and grows more nutritious, more resilient crops,” says Schultz.

That involves cover-cropping, composting, moving animals around the land, and minimal tillage. Red Shirt even eschews organic pesticides “because they can kill beneficial insects and native pollinators,” says Schultz, who thinks “organic standards are a joke” because they don’t go far enough. “There’s no real emphasis on soil health, no emphasis on animal welfare,” he says.

Nonetheless, he is currently working on the farm’s organic certification, primarily because it is a prerequisite for the add-on certification he truly desires from the farmer-led Real Organic Project, started by what Schultz calls “the old guard in the movement.”

Under Real Organic, Schultz explains, “farmers, your colleagues, will come around and assess whether the farm meets these augmented standards.” For instance, Real Organic requires chickens to be pasture raised, while USDA will certify as organic eggs from chickens that have never been outside.

With the opening of Schultz’s farm store this summer, he hopes to add one more component to fulfilling his vision: helping other small farmers to realize their own dreams. It’s difficult for these farmers to find outlets for their products since conventional distributors aren’t able to carry their smaller output. Schultz, like his farming colleagues, sells through a CSA and at farmers markets. The Red Shirt CSA now has between 100 and 150 members. But now, with the opening of his store on well-trafficked Route 7, he can showcase his products—and those of other farmers—for customers unable to visit farmers markets at set times or commit to weekly CSA offerings.

Schultz plans to sell meat, poultry, lamb, pork, eggs and dairy, as well as produce in what Schultz describes as “a highly curated mini-grocery.”

Standing in the store’s roughed-out open space, Schultz points to an area that will become a commercial kitchen, allowing him and other farmers to make micro-batches of value-added products, such as a case of salsa. The kitchen is likely to be ready later in the summer, and Schultz says he has already received inquiries from a chocolatier, a chef who wants to do cooking classes, and an organization that works with food pantries.

COMMUNITY SUPPORT

There has been an outpouring of support for Schultz’s expansion. So far, he’s received approximately $700,000 in state and federal grants, and he’s waiting to hear about other grants for a cooler, a flash freezer, and a generator. And crowdsourcing raised another $20,000, plus an additional $40,000 through a two-to-one match from Massachusetts Growth Capital Corporation. “I think people see that it’s a concept that they want—fresh, local food,” says Schultz. “If I didn’t do this, the gap would be filled by another supermarket or a bigger producer that wouldn’t really meet that need for super hyper-fresh produce. Wouldn’t it be great if we pick it in the morning, bring it here within hours, and then it was out on the shelf?”

Along with local community members, Schultz also plans to offer classes in such subjects as food preservation, canning, and ethnic cuisine. He anticipates overseeing the store while Sarah French, his co-farmer and partner, handles the farm operation.

Additionally, Schultz hired Noreen O’Connor, who had worked in a similar retail operation on Martha’s Vineyard, to help launch the store. But she will also have responsibilities for growing and picking produce. “We just need that many hands on our pick days,” Schultz says, adding that the hands-on work will also help O’Connor speak authoritatively about what’s in the store. At a time when most small farmers are struggling to find help, Schultz is thankful to have four others working for him this year and is somewhat incredulous that “they approached us. None of them has farm experience, but they are just really good people, which is what you want anyway.”

WORTH WAITING FOR

As he sits at the cusp of a reinvented and expanded Red Shirt Farm, I think back to a previous visit to Red Shirt. As we sat around Schultz’s kitchen table, he started talking excitedly about growing ginger. “What people think is ginger doesn’t look like it at all,” Schultz says. “It’s beautiful. When it’s really fresh, it’s gorgeous, pink, white, orange, vibrant looking, and much different tasting, too, more piquant.” He told us that you’ve got to keep new ginger at 90 degrees and at 90% humidity for about six weeks in the greenhouse before planting it outside. “And it takes the entire season,” he says. “By September, it’s ready.” And worth waiting for, not unlike the realization of Schultz’s own dream. “We could not have pulled this off on our own,” he says. “I think it’s going to be a huge resource for our community and our fellow farmers.”