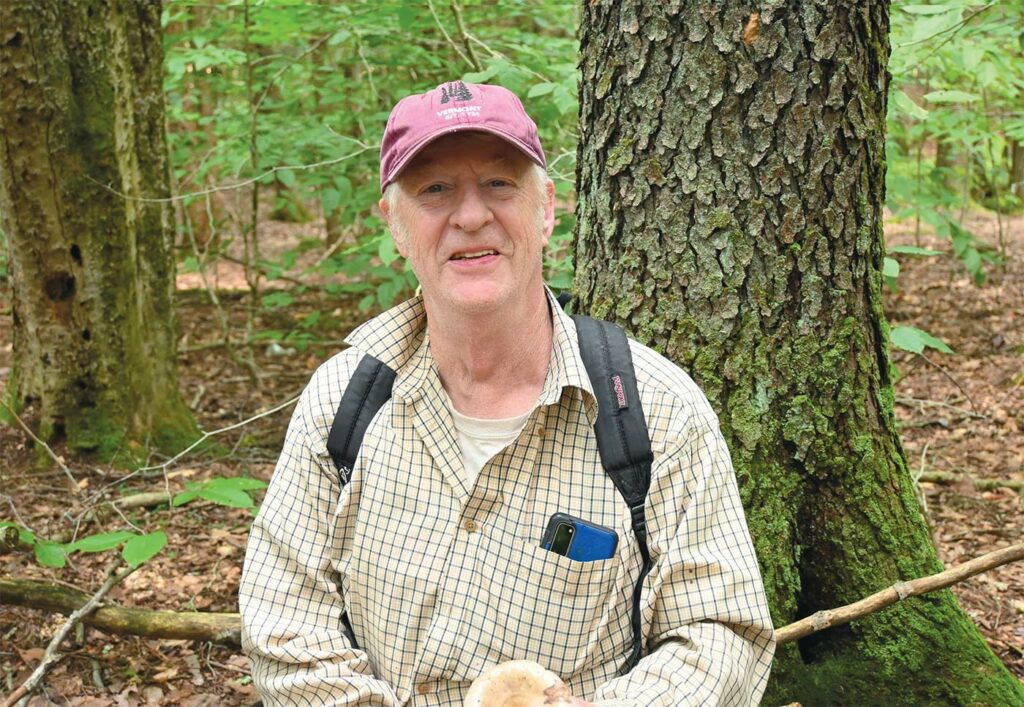

A Walk in the Woods with John Wheeler

PHOTOS BY JOHN WHEELER

John Wheeler takes his mushrooms very seriously. He had better. Most mornings, the 68-yearold Berkshire native and founder of Berkshire Mycological Society chops up a bit of foraged fungi and adds it to whatever’s on the menu. “I cooked up some black trumpets and eggs this morning,” he says. “They’re like poor man’s truffles.”

Just about every Sunday morning, from April to November, John leads a group of mushroom enthusiasts on a forest walk to learn, discover, and talk about mushrooms for a couple of hours. The walk starts at 10am but he won’t disclose the exact location, posted on Berkshire Mycological Society’s Facebook page, until 8:30. Why? Because he discovered that commercial foragers were watching his page and “poaching the patches.” And so, his devotees rise early and wait for the big reveal.

We joined him in late July after being summoned to the parking lot behind Mount Everett Regional School in Sheffield. “Come prepared to bleed,” he cautioned on Facebook. He wasn’t kidding. A mushroom hunt is always more fruitful after a soaking rain, but you must be prepared to battle clouds of mosquitos. Twenty or so of us, doused with our repellent of choice, gathered at a picnic table with our woven baskets and brown paper bags, hoping that the haul would be worth the inevitable onslaught. There were first-timers, veterans for whom this was clearly a Sunday morning routine, a kid carried high on a dad’s shoulders, some visitors from the West Coast, and someone who jokingly claimed to be in the witness protection program.

There’s an old saying: “All mushrooms are edible, but some only once.” It’s dark humor but should be taken to heart. Oysters, morels, maitakes, chanterelles, trumpets—all abundant in Berkshire forests—delight the palate. But slip up and misidentify and you might well end up in the ER, or worse. We happen upon just such a species early on. “This is a destroying angel and it’s about as bad as it gets,” John says, pointing to an innocuous-looking white mushroom with a long stem. This one can kill you.

‘I’M IN IT FOR THE EASTER EGG HUNT’

While most of our fellow hunters are out looking for choice edibles, John makes it clear that he’s not solely a forager. While he loves eating mushrooms (he’s never become ill, he says), he’s in it more for the “Easter egg hunt.” How many species can he find in a single walk? What new information can be garnered from what he discovers on the forest floor? With every walk, there’s the possibility that he might add to the count of mushroom species he’s found in the Berkshires in his 35 years as a mushroom hunter: 1,100 to date.

John got hooked on mushrooms the day after a night out at Mundy’s—the now-defunct rough-and-tumble bar of Berkshire lore, situated in Glendale, just down the road from Stockbridge. “I gave a guy a ride home to get him out of the bartender’s hair,” recalls John. “And the next day he asked me for a ride to pick mushrooms.” So, they picked Honey mushrooms, as well as bear’s head tooth (which tastes like crabmeat), cooked them up, and had a feast. “I thought ‘Why would anyone eat store-bought mushrooms if you can get something that tastes like this in the wild?’” John says. “I immediately went out and bought an Audubon book and started picking mushrooms every weekend.”

His decades-old passion has driven him to accumulate encyclopedic knowledge of mushrooms, enhanced by classes that his wife, Judy—fearful that his enthusiasm might lead to an untimely demise—insisted he take. Over the course of their 34-year marriage, she’s given him a mushroom book every birthday, Christmas, and Father’s Day. “I’ve got 150 or more and I read them all,” he says. “I’m constantly learning. I don’t want to spend a day when I’m not learning.”

AFOOT IN THE WOOD-WIDE WEB

John Wheeler seems to enjoy teaching as much as he does learning. On Facebook and in the forest, he has an audience eager to tap his expertise. Spend a couple of hours with him and it’s a bit like dipping your toes into a Mycelium 101 class. Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of mycelium, which form an underground mycorrhizal network that’s intertwined with tree roots. That network connects plants and trees, and sends them information, water, and nutrients that they share. In exchange, the mycorrhizal network uses the sugar it gets from the trees, converting it to energy that enables fruiting. This symbiotic relationship sparks respect and awe from enthusiasts, some of whom refer to the mycorrhizal network as the “wood-wide web.”

Certain species of mushrooms are partial to specific trees, John explains, so location is one the factors that contributes to correct identification. For instance, hen-of-the-woods prefer hardwood, particularly oak (or even underground rotting stumps); the porcini group prefers conifer forests but can grow on hardwood; lion’s mane is most frequently found on dead beech; oysters grow on living and damaged trees or fallen branches; puffballs are found on grass. Aroma, says John, is also a strong identifying factor. Some oyster mushrooms smell like fish; chanterelles are fruity; clitocybe smell like anise; the prince mushroom smells almondy.

After so many years of examining the forest floor, John thinks he has “an internal guidance system” that helps him identify mushrooms. Most people don’t. So, caution is imperative. Don’t use this article (or ANY single article or any online resource) to identify a mushroom you’re planning to eat. Be mindful of bugs, and take note of the environment, as mushrooms are very good at accumulating toxic elements such as heavy metals. Beware of mushrooms growing near galvanized fences or dumps, or even the side of road, where they may be contaminated by car exhaust or canine leg-lifting. Also, be aware that some mushrooms can interact with prescription medications, such as blood pressure meds or SSRIs; some folks may also have sensitivities or allergies to specific mushrooms. Always cook your mushrooms before eating and take a small bite first!

A good resource to get you started on your own mushroom journey is the original National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms, written by renowned mycologist and naturalist Gary Lincoff. Also, consider joining the Berkshire Mycological Society Facebook page, which contains a treasure trove of mushroom info.

MUSHROOMS TO LOOK OUT FOR

Here are a few edible species you may want to keep a lookout for this fall:

Hen-of-the-woods (Grifola frondosa), also called maitake. Commonly found at the base of oak trees, this mushroom grows in clusters of grey-brown fronds. The inner flesh is white. Great for sautéing and stewing, Maitake is also known for its medicinal properties.

Oysters (Pleurotus ostreatus) are oyster- or fan-shaped, grow in smooth, overlapping clusters, and are often found on dead or decaying sugar maple. They can smell like fish. Delicious in soups and sauces, Oysters may also contribute to heart health.

Puffballs (Lycoperdon perlatum) are round and smooth with no stems or gills, and most often found in the grass. Immature Puffballs share some characteristics with the death cap mushroom so proceed with caution. If it’s big, smooth, and solid white on the inside, it’s most likely a puffball. John calls puffballs “poor man’s tofu” because they don’t have a distinctive flavor of their own, but rather take on the taste of whatever they’re cooked with.

Chicken-of-the-woods (Laetiporus sulphureus) are not the same as hen-of-the-woods. They’re golden or bright orange, shelf-like mushrooms that grow on hardwood tree trunks and branches. They can be used as a substitute in chicken dishes and may lower blood sugar, so diabetics should be careful.

Lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus) looks like a white shaggy beard or mane and grows on hardwoods such as walnut, beech, maple, and birch. This delicious edible is also reported to have medicinal properties that benefit the brain, heart, and gut.

Porcini (boletus edulis) is a prized mushroom that grows at the base of living hardwood trees and sometimes conifers, such as the Norway spruce. It has a cap in shades of brown, a meaty stem, and a sweet, earthy aroma. Often called “the king of mushrooms,” Porcini are favored by chefs and also are reported to have anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties.

Hedgehog or sweet tooth (Hydnum repandum) are found in hemlock forests. They have yellow or tan caps and are most easily identified by vertical, white, spiny teeth under the cap. Sautéing with butter and onion brings out their sweet, nutty taste.