The reward (Photo by Jonathan Doster for the Hotchkiss School)

By Emily Armstrong Oberto

It’s a cool New England morning. A crackle of frost covers the fields, glinting as the sun comes over the ridge. You take in a cleansing breath and set to work bringing the cows in for milking. Your muck boots crunch on the crystalline grass as you encourage the herd towards the dairy. Though your mind is present on the task at hand, you prepare for the busy day ahead—breakfast in the dining hall, a math exam, the soccer game after school…

While not yet a mainstream activity, experiences like this one are becoming a curricular component at a growing number of schools in the region. In certain cases these endeavors may owe something to the resurgence of the “back to the land” movement or the work of such food luminaries as Alice Waters, patron saint of school gardens, or food journalists like Michael Pollan. In other cases, student farming is a return to an institution’s own pastoral history or the result of the explosive flowering of teenage creativity.

Regardless of their origins, these programs each use experiential learning to connect students in some way with the land, their community and the food they eat.

Cracking the books (Photo courtesy of the Putney School)

The Putney School,

Putney, VT

Putney is one of the pioneers of student farming, and manual labor is a central aspect of life there, given an honored place alongside the traditional classroom experience. While Putney’s progressive mission stretches broadly, addressing societal issues beyond the food system, much of the work students do supports sustainable food production on campus.

Among other assignments, students work in the barn milking cows, take part in maple sugaring and cider making or help harvest produce from Putney’s six gardens, which cover an acre and a half of campus land. Or they support in the preparation and serving of meals. A collaboration with local cheesemakers, Consider Bardwell, is even in the works.

According to Putney’s gardener and farm assistant, Katie Ross, anywhere from 10% to 20% of food on the school’s menu comes directly from its own soil or animals. “So much gets used,” she said, “it’s almost too much to label.” Taken together with courses like “Complex Systems: Agroecology” and “Foods Around the World,” Putney puts a farm-and-classroom-to-table philosophy into practice.

Farming is in Putney’s DNA and the lessons of living, working and playing on a farm have a lasting impact. Pete Stickney, Putney’s farm manager, explains, “The school was intentionally founded as a farm, a farm with a school on it. I think we have a lot of kids who stay involved in raising gardens, or know their local farmer, or have an ethos around buying food. They are exposed to a lot of classes about the environmental and human impact of food and a lot of Putney students leave with that awareness. Putney hasn’t bothered to brand it—we’ve been doing this long before locavore or sustainable were even words.”

Students at Northfield Mount Hermon School celebrate the birthday of farm program

director Liam Sullivan. The photo is by Eva Laubach who blogs about the farm

at Nmhfarm.wordpress.com

Northfield Mount Hermon School,

Mount Hermon, MA

Like Putney, the Northfield Mount Hermon School (NMH) was founded with a mission that included manual labor, although one with very different roots. NMH began as two Christian schools for underprivileged students—Northfield for girls and Mount Hermon for boys—each of which stressed the importance of working by hand for several hours each week. For Liam Sullivan, director of the farm program and an NMH alumnus, the school’s current farming opportunities are a reëxpression of its earliest values. “It was once a big farm with a little school; now it’s a big school with a little farm. Back in the early days the boys milked about 100 cows and grew all their own food.”

By the 1980s, after Big Ag became entrenched in this country, the NMH farm fell into disuse, but Sullivan’s predecessor, Richard Odman, took the remaining farm club and gradually rebuilt the program. Today the farm represents a small but robust part of school life, with around 40 students each term helping to manage a small herd of grass-fed Jersey cows and the accompanying dairy, the smallest licensed outfit in the state. They are also involved in food production, including sugaring, as well as making cider, cheese and ice cream— their wares are for sale on the school’s website.

The farm is also a “living lab,” providing hands-on learning opportunities for students in academic classes, and though some students may pay little attention to the farm, for others it is a sanctuary. For Sullivan, having grown up on a farm, the NMH program ultimately helped him learn about himself, and influenced his decision to study environment and agriculture in college at UMass-Amherst.

Extending the season at Monument Valley High School

(Photo by Dylan Cole-Kink)

Monument Mountain High School,

Great Barrington, MA

In contrast to these mission-driven farming programs, Monument Mountain’s Project Sprout is something quite different. The brainchild of three inspired Spartan students Natalie Akers, Sam Levin, and Sarah Steadman, PS is all about the power of teenagers to create positive change. The original goal was to build an organic garden to feed the schools in their district and provide educational connections between students and the natural world. In under a year, and with a dramatic input of energy, enthusiasm and resources from its founders and the community, Project Sprout became a reality, with fresh produce reaching the Monument Mountain cafeteria, and kindergartners visiting the garden weekly. The bumper crop even stretched far enough to feed hungry families in the area.

Several years on, PS’s founders have graduated, but the garden continues under the watchful eye of guidance counselor Mike Powell. There from PS’s thrilling beginning, he now helps current students manage the 12,000-square-foot plot, berry patch, fruit orchard and hoop house. While he acknowledges that the program’s rapid expansion has been challenging at times to contend with, Powell remains amazed by all that can be accomplished when young people combine their passion, intelligence and fearlessness. These days PS is searching for better ways to make use of their abundance, much of which is harvested in the summer months. They are in discussions with the Berkshire Co-op to trade some of their summer produce in exchange for fresh fruits and vegetables later in the school year so that Monument Mountain students can benefit from fresh, healthy food year-round.

Although some of PS’s initial goals have stalled somewhat, most notably collaboration with other district schools, Powell is heartened by the continued student energy that powers the program. PS has also helped support related student initiatives, like the new Food Committee, which works to bring several all-local menus to the cafeteria each year. Without a doubt, the emergence of the PS garden has had a lasting impact, not only on Powell and the student founders, but others who have passed hours working in the garden. Many students have gone on to study environmental science, and one Monument Mountain grad is currently enrolled in Cornell’s esteemed agricultural program, focusing on environmental policy.

“It was a student idea … and is largely student-run,” says Powell, and so he accepts that the students change as the garden does—with the seasons. To schools contemplating a garden of their own, he encourages starting small.

“One thing I’ve learned: Whatever you plan to do with your garden, pick what you are going to do and do it well.”

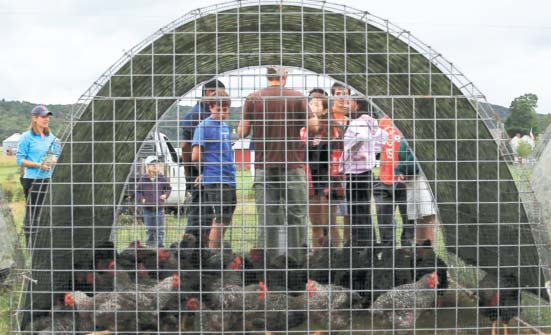

Fowl class at the Hotchkiss School, Lakeville, CT

(Photo by Jonathan Doster for the Hotchkiss School)

The Hotchkiss School,

Lakeville, CT

A relative newcomer to the school farm scene is the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, CT. About eight years ago alumnus Jack Blum arranged the transfer of Fairfield Farm to his alma mater, and an exciting spectrum of educational prospects sprang to life. Founded in the late 1800s, Hotchkiss had little agricultural history to speak of, though the school has long had a commitment to the stewardship of its rich natural environment.

It was in these local ecosystems and not farming that Charlie Noyes, Hotchkiss visual arts instructor and farm curriculum coordinator, rooted his proposal for FFEAT, the Fairfield Farm Ecosystem Adventure Team, a co-curricular option for students. At it inception, FFEAT members explored the natural world—birding, working with field botanists and clearing trails. Today, farming and food production are FFEAT’s focus.

Students working on the farm plant and harvest produce, which includes 37 crops currently in rotation. They also have opportunities to interact with the pigs and poultry raised for use in the dining hall—last year, some even learned how to slaughter chickens with Allen Cockerline, a local grass-fed cattle farmer who provides oversight. The school has put incredible resources towards building up both curricular and culinary connections between the farm and its main campus, with great attention paid to the balance between production and education. Sometimes there is just grunt work to be done, while at other points time is given to experiential reflection or socializing at the farm. According to Noyes, “It doesn’t matter who you are. Anybody who goes out there for more than five minutes gets hooked. It’s beautiful.”

The farm team also includes John Hahn, associate head of school for environmental initiatives; Kurt Hink, alumnus and farm manager; and Andrew Cox, Sodexo’s dining services general manager and director of sustainability. Under Cox’s leadership, this semester Hotchkiss saved over $11,000 by using the produce from the farm, and to date is donating about 10% of its harvest to local food banks. Additionally, the arrival of Cox last year signaled a greater commitment to sustainability in the dining hall—he has helped procure 37% of Hotchkiss’s food from local sources, an almost 100% increase in a year. With a grant secured recently, Hotchkiss intends to build a food processing and storage facility at the farm aimed at significantly increasing food production in years to come.

But as much as Fairfield Farm is changing the community’s experience in the dining hall, it is still very much about giving students contact with the land. Hotchkiss alumna and three-year FFEAT veteran Anne Gifford spoke of her powerful school-farming experiences: “ I returned to FFEAT year in and year out because I felt like my activity benefitted the community in a very palpable way. The food FFEAT planted and harvested appeared in the dining hall throughout the year, nourishing the students, faculty and staff. I hope to become involved in farming initiatives in urban Chicago, and my time with FFEAT definitely contributed to this desire.”

Kristin Wolfe, a student at Mount Everett, trims the hooves of a goat

named Moon. (Photo by Danielle Melino)

Mount Everett,

Sheffield, MA

Surrounded by an array of small farms, Mount Everett students are positioned well to get their hands dirty in the world of animal science. Teacher Danielle Melino, who holds both undergraduate and master’s degree in agriculture education, is passionate about her course, which gives both experienced farm children and absolute beginners a solid foundation in ag history and economics, as well as animal health and husbandry. Whether in the course or not, Mount Everett students are eligible to join the Future Farmers of America (FFA) chapter, and Melino hopes involved students will show their animals at the Sheffield Fair this year.

In addition to classroom time, Melino’s course includes a significant experiential component. There is a barn on campus housing sheep, a few goats and four alpacas, which the students learn to care for. In the spring, there will be lambs. Students participate in field trips, and are also required to complete a supervised ag experience (SAE), an internship at a local farm. Currently students are working with Dominic Palumbo at Moon in the Pond, as well as at Pine Island and Taft Farms among others. Beyond providing practical and service learning opportunities, the SAE teaches leadership and responsibility and gives students a sense of career possibilities.

Melino, who is in her second year at the school, has high hopes for the program—she would love to add another section of her course, have student-raised lamb served in the school cafeteria, expand the flock to include heritage breed Shropshires, increase the time commitment of the SAE, expand the school’s annual ag fair and, most importantly, involve younger students. All of this takes resources, which are in short supply, but Melino is a strong advocate for the importance of ag literacy for this generation of young people.

By increasing the sustainability of their institutional food systems, school farm initiatives like these are an encouraging development in the landscape. But the value of student farming is wide-ranging and impossible to quantify in bushels of kale. Beyond pumping organic milk, meat and produce into the cafeteria, student farm programs are providing food to hungry families in the region, building relationships with local farmers, encouraging an appreciation for the rugged beauty of farm life, instilling critical leadership and literacy skills, highlighting the noble power of physical labor and hopefully inspiring a generation of students to consider careers in the environmental or agricultural sectors. Each in its own way, these institutions—and many others besides—are marrying a respect for New England’s agricultural heritage with very pressing concerns about the health of our children, the natural world and our food systems. With young people leading the way, the harvest is bound to be bountiful and delicious.

Emily Armstrong Oberto, mother of two amazing children, is a scattered home cook, apprentice cheesemonger, wannabe world traveler and committed Italophile. She recently earned her masters’s degree through New York University’s Food Studies program. With a background in secondary schools, she is interested in the ways we teach young people about real food and good taste.

Emily Armstrong Oberto, mother of two amazing children, is a scattered home cook, apprentice cheesemonger, wannabe world traveler and committed Italophile. She recently earned her masters’s degree through New York University’s Food Studies program. With a background in secondary schools, she is interested in the ways we teach young people about real food and good taste.